How big does a video content distributor have to be, to gain the upper hand in licensing deals with content owners? The answer matters where it comes to any potentially big changes in video entertainment distribution.

How big does a video content distributor have to be, to gain the upper hand in licensing deals with content owners? The answer matters where it comes to any potentially big changes in video entertainment distribution. Up to this point, even the largest U.S. cable operators, though able to win volume discounts, have not had the dominant role in the business relationship, at least in recent decades, one might argue. The largest programmers, with the "anchor" channels, essentially have been able to dictate placement on programming tiers and force bundling of multiple networks.

In other words, contracts generally forbid sales of channels a la carte, which would represent one potential source of innovation. So far, Comcast, Time Warner Cable, AT&T, DirecTV, Dish Network, Verizon and others have lacked leverage.

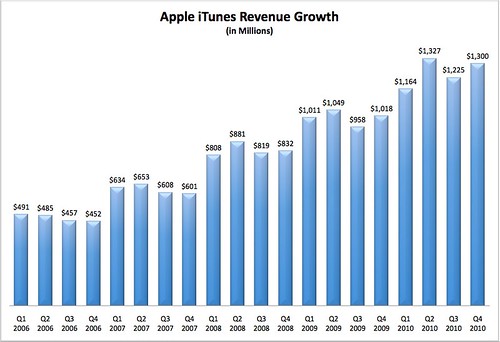

But then there's Google, Apple and Amazon. Apple's iTunes customer base arguably got to be so large that music publishers had to do business with Apple, on the general terms Apple wanted. That includes such basic matters as retail pricing, royalty rates and ability to "unbundle" discs and sell songs one at a time.

Video content owners "learned" from that experience and do their best to avoid ceding power to the newer distributors. But some might argue that some distributors have potential to grow so large that the potential audience simply cannot be ignored.

Video content owners "learned" from that experience and do their best to avoid ceding power to the newer distributors. But some might argue that some distributors have potential to grow so large that the potential audience simply cannot be ignored.

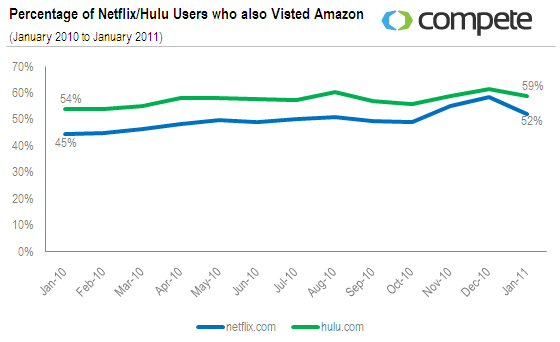

Some might argue that, over time, content owners "must" lose power to the huge new distributors. In that view, Amazon, Apple and possibly some others will amass audiences so large that the distributors will gain the upper hand. Who "owns" video distribution?

Certainly many would argue that perpetual annual price increases for video entertainment services at their current rate are unsustainable. And one almost-certain way to put a brake on costs is for distributors to gain the ability to say "no" to programmer demands.

Network economics would change, of course. If programmers cannot "force" distributors to buy channel bundles, and distributors do not restrict channel bundles so rigidly, programming choices could explode.

Though telco, cable and satellite distributors might not prefer to sell smaller packages of channels, or simply programs, newer distributors might well prefer to sell that way. Think iTunes rather than a Comcast video subscription.

Many lightly-viewed networks would no longer be viable. Many shows would have a harder time getting exposure to an audience. But new promotion methods would arise. YouTube Channels might become more important venues for specialty networks.

Some might question the long-term viability of the channel metaphor. But channels are akin to "genres" of music. People have favorite artists and songs. But they also have preferences for genres. The same will be true for video and movies. Both channels and a la carte can coexist.

Cable operators, though, are not likely to be as supportive of a la carte access to discrete programs as will Amazon and Apple, who have device and business ecosystems well suited to a la carte buying. Apple and Amazon have numerous other ways to make money than by selling advertising.

Video distributors make money on subscriptions and advertising, and both revenue streams potentially are disrupted by a la carte sales.

But the question remains: how big does a distributor have to be before content providers must be on the platform? In music, the answer has been "as big as Apple." So far, nobody in the video distribution business has yet reached that scale, apparently.

But there are lots of potentially-huge channels. In the online world, Apple, Amazon and Google might come to mind. In the physical world, Wal-Mart, Target or Best Buy already have tried to make a move. So far, though, all we have seen is cracks. The old order is not yet crumbling.

In other words, contracts generally forbid sales of channels a la carte, which would represent one potential source of innovation. So far, Comcast, Time Warner Cable, AT&T, DirecTV, Dish Network, Verizon and others have lacked leverage.

But then there's Google, Apple and Amazon. Apple's iTunes customer base arguably got to be so large that music publishers had to do business with Apple, on the general terms Apple wanted. That includes such basic matters as retail pricing, royalty rates and ability to "unbundle" discs and sell songs one at a time.

Some might argue that, over time, content owners "must" lose power to the huge new distributors. In that view, Amazon, Apple and possibly some others will amass audiences so large that the distributors will gain the upper hand. Who "owns" video distribution?

Certainly many would argue that perpetual annual price increases for video entertainment services at their current rate are unsustainable. And one almost-certain way to put a brake on costs is for distributors to gain the ability to say "no" to programmer demands.

Network economics would change, of course. If programmers cannot "force" distributors to buy channel bundles, and distributors do not restrict channel bundles so rigidly, programming choices could explode.

Though telco, cable and satellite distributors might not prefer to sell smaller packages of channels, or simply programs, newer distributors might well prefer to sell that way. Think iTunes rather than a Comcast video subscription.

Many lightly-viewed networks would no longer be viable. Many shows would have a harder time getting exposure to an audience. But new promotion methods would arise. YouTube Channels might become more important venues for specialty networks.

Some might question the long-term viability of the channel metaphor. But channels are akin to "genres" of music. People have favorite artists and songs. But they also have preferences for genres. The same will be true for video and movies. Both channels and a la carte can coexist.

Cable operators, though, are not likely to be as supportive of a la carte access to discrete programs as will Amazon and Apple, who have device and business ecosystems well suited to a la carte buying. Apple and Amazon have numerous other ways to make money than by selling advertising.

Video distributors make money on subscriptions and advertising, and both revenue streams potentially are disrupted by a la carte sales.

But the question remains: how big does a distributor have to be before content providers must be on the platform? In music, the answer has been "as big as Apple." So far, nobody in the video distribution business has yet reached that scale, apparently.

But there are lots of potentially-huge channels. In the online world, Apple, Amazon and Google might come to mind. In the physical world, Wal-Mart, Target or Best Buy already have tried to make a move. So far, though, all we have seen is cracks. The old order is not yet crumbling.

No comments:

Post a Comment